Richard Gere and Brooke Adams in “Days of Heaven”

Photo by Bruno Engler. Paramount Pictures/Photofest

The following piece about Art Center Film faculty member, Billy Weber, was originally published in the September-October 2013 issue of Editors Guild Magazine

Terrence Malick’s “Days of Heaven” (1978) was, and remains, a riveting film. From the opening montage of period stills accompanied by Saint-Saens’ musical suite, “The Carnival of the Animals” to the final shot of young Linda Manz’s character skipping off into an unknown future, the film has an emotional, almost hypnotic, pull that never lets up.

The editing is such that practically every cut brings a new flood of information, in an elliptical style in which image and naturalistic sounds take precedence over dialogue. And yet, despite the lack of normal storytelling convention, the film packs an emotional wallop unlike very many movies in history. Released 35 years ago this September through Paramount Pictures, “Days of Heaven” introduced a new style of storytelling to the American cinema, albeit one that has not been widely imitated.

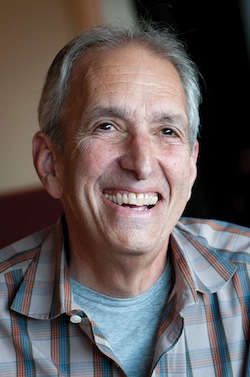

Billy Weber at his home in Silverlake.

Photo by Barbara Katz

All of this came about through lots of hard work on the part of writer-director Malick and editor Billy Weber, who are longtime collaborators, dating back to Malick’s feature debut, “Badlands” (1973), and are currently working on his Voyage of Time. Starring Richard Gere, Brooke Adams and Sam Shepard, “Days of Heaven” evolved from a conventionally scripted story of a love triangle into something much different — and greater.

“When we had cut it together as a full-on dialogue movie, it wasn’t turning out the way we had hoped,” recalls Weber in a recent interview with CineMontage. “So we wanted to take a different approach to it — but we didn’t know what that approach should be. Terry would tell you today that it was the hardest we ever worked in our lives.”

Weber and Malick delved deeper, working seven days a week for a year, experimenting and turning over many ideas until a new style slowly took shape and the movie came to be what it is today. The style and the rhythm were discovered in post-production.

Regarding the distinctive style of the film, Weber reveals, “We never thought of it as a new vocabulary. All we thought was, ‘How can we make this movie releasable?’ How can we cut this movie so that people will watch it, appreciate it and like it?’ We were very nervous. What I was doing almost all of the time was trying to find isolated shots from anywhere in the movie that could be used to convey one thing.”

Shots were taken completely out of context in order to illuminate the story in a way not originally intended, according to the editor. The juxtaposition of these images led to deeper feelings, and gave a new direction to the story.

“Out of necessity, we had to tell the story in a way that worked better, and that process showed us how to make that movie,” Weber explains. “Both of us felt like we were out in the woods and didn’t know when we were going to find life. But then we reached a point in the cutting where, when we screened the movie one night, we finally saw where to go; it suddenly became clear what we had.

“Ultimately, I learned all I know about editing on that movie, in terms of the best filmic way to tell a story — which is without dialogue,” he continues. “If you can do that, then whatever dialogue you do have is like the icing on the cake. As an example, in the eight- or nine-minute sequence from the time Gere leaves the farm with the flying circus to the beginning of the wheat fire, there are only three or four lines of dialogue.”

A key element of the movie is the narration by actress Manz, a 15-year-old discovery from the New York public school system. Her narration brings a quirky, tough-yet-innocent quality to the film. Interestingly, the film is not presented as being strictly from her point of view. Instead, she comments on the action, or gives her perception of what is occurring.

Says Weber, “Linda had such a unique style about her that was so honest. At first, Terry wrote a lot of voiceover for her to read, but it felt written; it felt like it wasn’t Linda.” One night, Malick had Manz over to his place to record more narration onto a Nagra, but she insisted on sharing her version of the Apocalypse story from the Bible — which she had heard read aloud by a woman at the house where she had been staying.

“Eleven o’clock that night, I’m at work and Terry calls me asking for more quarter-inch tape, saying, ‘You’re not going to believe what’s happening here,’” remembers Weber. “That’s when he realized that we needed Linda’s version of what was going on. He decided to start showing her scenes from the movie, then stopping and asking her to tell her version of what just happened.”

Other narration was written to more accurately reflect Manz’s distinctive voice, a streetwise New York accent. In all, over 60 hours of narration was recorded. After much experimentation and debate, 15 minutes of it was ultimately used.

“People who haven’t done movies with voiceover don’t realize what an enormous element it is,” explains Weber. “It’s like music — it changes the rhythm and it changes the cut. All of a sudden, that becomes the rhythm of the movie. We would often have 60 different versions of a line. We were cutting on the KEM, but would listen to the narration on a Moviola; it was just easier. During the mix, we would sometimes play a reel while trying out a line of narration against different areas until we found a spot where it felt right.”

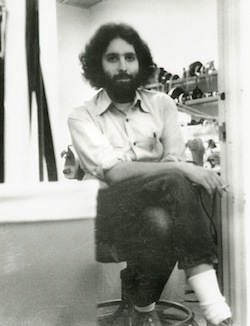

Billy Weber working on Days of Heaven, circa 1978.

The use of sound in “Days of Heaven” is striking. The sounds of the environment often take center stage, with no accompanying music or dialogue. Some of the sound credits include those for special environmental sound recordings, special sound effects and special audio assistance. “My assistant Jim Cox created many of the sounds,” says Weber. “The sound of the windmill on the roof is the sound of a dubbing stage patch cord being swung around in front of the microphone. We did some synth stuff for the sound of one of the tractor engines because it gave us a great low end that we couldn’t get from the real tractor.”

Late in the film, there is a sequence of a locust attack on the farm, which leads to the accidental burning of the wheat field. Building slowly from the first appearance of the locusts into a raging conflagration that is heartbreaking in its intensity, it is the turning point of the movie for all of the characters and leads directly to the dissolution of every relationship.

Days of Heaven was pre-CGI, so the filmmakers had to come up with all sorts of creative ways to achieve a desired effect. There are two stunning shots of swarms of locusts shooting from the wheat field to the sky as the characters helplessly watch. According to the editor, this was achieved by running the film backwards through the camera as a load of nutshells was dropped from a helicopter, the actors following them with their head movement. When the film is projected forward, it looks as though the actors are tilting their heads toward the sky as a huge cloud of locusts flies up. Footage involving the locusts was filmed in several locations in Montana and Canada over a period of months.

Weber and Malick had approximately 125,000 feet of film to cut — a minimal amount by today’s standards. The budget was $3 million, which, compared to the concurrently filming Sorcerer (also for Paramount), was very low. Consequently, the filmmakers never heard from the studio. Executives did not see the film until it was done — unheard of today — and the reaction was very positive.

According to Weber, the legendary Charles Bluhdorn, chairman of Gulf + Western, then owner of Paramount, told Malick, “I don’t care if your movies never make a nickel. I want you making movies for me.” As fate would have it, 20 years would pass before Malick would make another film — 1998’s “The Thin Red Line,” with Weber again in the editor’s chair, but it was for 20th Century Fox.

Reiterates Weber in conclusion, “Everything I have done in editing since then was influenced by what I learned on ‘Days of Heaven.’”