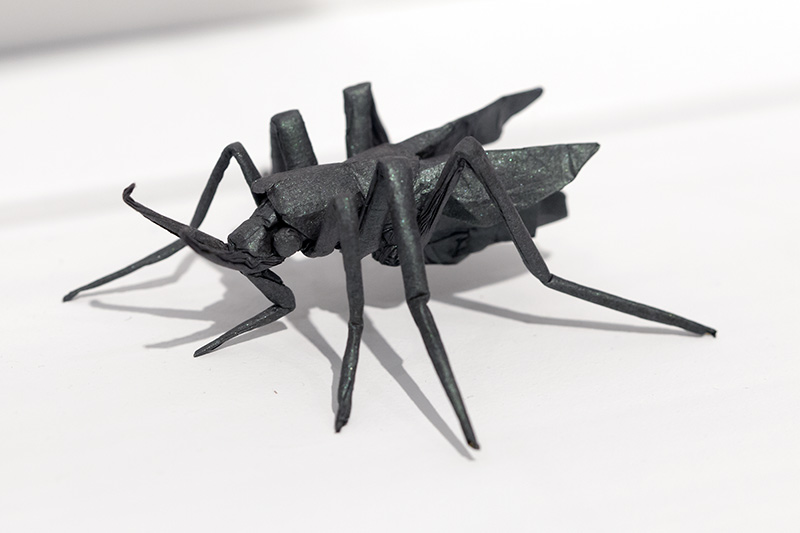

Origami seems an odd and roundabout way to arrive at the realistic likeness of a scorpion. Clay would be faster, more direct, less convoluted. And yet there’s an edgy charm to it—the calculated, maybe obsessive, brain teasingly affectionate practice of folding paper. It is, in essence, design. Good design.

It’s an old process. After paper was invented in about the 2nd century CE, it took another 400 years to migrate from China to Japan, and a few centuries more to infiltrate Europe. Folding followed along, creased and sharp, and largely ignored as a serious art until the middle of the last century when poverty-stricken factory-worker dropout Akira Yoshizawa changed everything. His experimentation risked tradition, and his introduction of a wet-folding technique expanded origami’s visual vocabulary, inviting greater artistic expression.

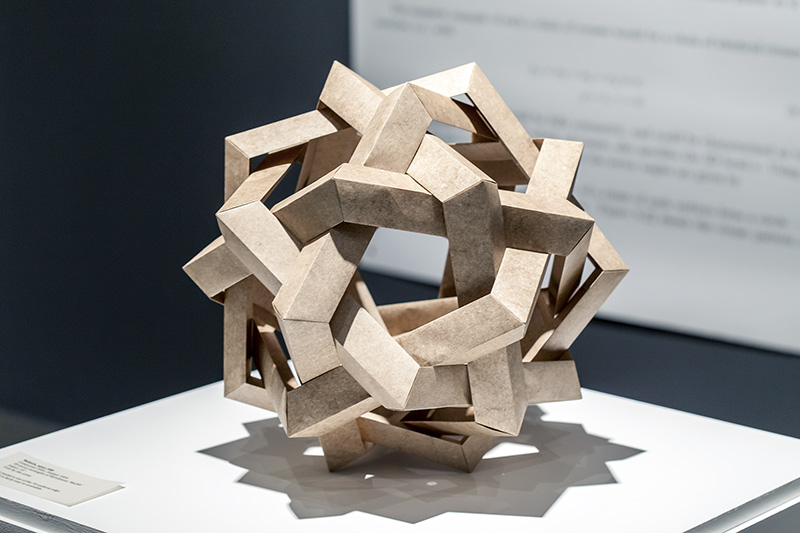

There’s a Möbius mystery to the flat paper plane, an allure. It’s a magical tension between what is expected and what is delivered, perhaps deeply ingrained in us by the ancient and visceral illusion of a flat horizon denied by our planet’s spherical reality. We evolved here, after all, wondering—flat, yet not-flat. “The art of contradiction and conflict,” is how mathematician, physicist, and origami master Robert Lang puts it. Paper is a flat plane we just can’t resist questioning and disturbing.

My friend the curator Meher McArthur, an expert in Asian art forms, visited Art Center a couple years ago and suggested we collaborate on an origami exhibit. The Williamson Gallery explores, among other things, the notion that design is aptly defined as a creative process realized at the intersection of art and science. Robert Lang is a scientist whose passion for origami has integrated those two domains in near equal proportions, and so the exhibition that emerged from Meher’s visit was this co-curated solo display of Robert’s work and process. The show glimpses a complex design cosmos, one concealed in the folds of paper arthropods and arachnids. Folds matter.

In another cosmos, the one studied by satellite-based telescopes, mirror-size is what matters. But launching a large intact mirror into orbit is risky business unless perhaps the mirror has been folded like origami on terra firma to then re-blossom in weightless space. Robert Lang continues to consult with scientists and is as equally challenged at the prospect of folding up hefty spacecraft as he is at the delicacy of fine paper. His research into how things compress has led to blurry boundaries between the mathematic and the aesthetic, the engineered and the sculpted. His is a process of foraging and working out, of thoughtfully deliberating, of inscribing new sensations of subtlety and nuance onto patterned form—in short, it’s design. Good design. Really, really good design. You should go see it.