It wasn’t the end of World War II, new job opportunities in the defense industry or the region’s cultural awakening that drew him to Los Angeles in the mid-1940s. It was the weather. “After I was discharged from the Navy, I went home to Ohio and then on to Detroit to work on the assembly line,” 86-year old Pasadena resident and Art Center alumnus Emerson Terry (ILLU ’53) recalls. “It was cold in Detroit, so my brother and I decided to move to Los Angeles.

“We arrived in Pasadena on New Year’s Eve in 1946. It was something, driving down the boulevard with people lined up along the street and banners flying in the air. Neither of us had heard of the Rose Parade before and we felt that spirit of celebration.” [ed. note: Art Center didn’t move to Pasadena until 1976.]

In 1948, when Terry was taking art classes at Los Angeles City College, a former classmate told him he had enrolled at the Art Center School (as the College was then known) and invited him to visit. “I was blown away by the quality of the students’ work,” Terry says of visiting the school’s Third Street campus in the Hancock Park neighborhood of Los Angeles. “I realized that type of artwork was what I really wanted to do, and I wasn’t going to learn it at City College.”

Having been admitted under the strength of his portfolio and the G.I. Bill, Terry began taking classes. “The Art Center experience was unlike anything being offered by other colleges or universities at the time. It really was a school where the instructors were all industry professionals. That in itself made the learning very concise. And I dare say, it was a different experience than learning from people who had only gone to school, matriculated and started teaching.”

Terry was among the first African-American students to attend Art Center. In fact, one of his fellow classmates, Bill Moffit, was both a friend from his earliest days in Los Angeles and also the first-ever African-American student admitted to the school. But according to Terry, the dearth of African-Americans on campus didn’t affect his experience. “I made new friends at Art Center and didn’t feel out of place. I was able to compare my abilities to other people’s abilities. That’s where we acknowledged each other’s differences: the quality of our work.”

While Art Center prided itself on providing its students a professional working environment, the real world was a bit different. “It was one thing to get into school with government money and a decent portfolio,” Terry stated. “But when it came time to take my portfolio and knock on the doors of studios and agencies—that’s when segregation and racism reared its ugly head. This was before the Civil Rights movement of the ‘60s. It was before Martin Luther King and sit-ins and fighting for inclusion.

“By the time I finished Art Center I felt I was a very capable artist. And while my instructors said I would do quite well, they failed to realize what circumstances I would face. It was very difficult for me to see my Caucasian friends walk right into job openings that I knew I was qualified for.”

Despite the challenges of the time, Terry went on to work with a number of prominent companies. His first full-time job was with aerospace firm Douglas Aircraft Company. “I used a lot of what I learned in Hamilton Quick’s perspective drawing class on that first job,” Terry recalls.

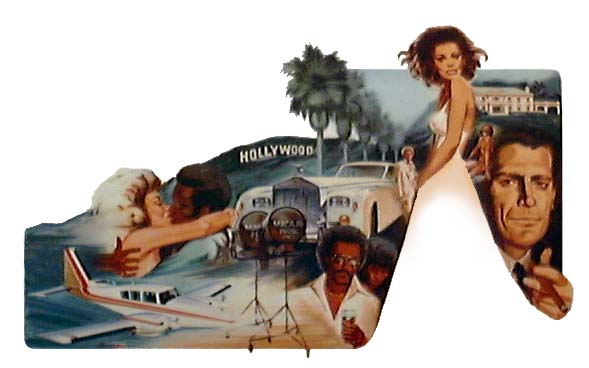

Other companies Terry worked for throughout his illustrious career include: Revell, a leader in plastic model kits; defense industry contractor General Dynamics; The Film Designers Division, and NBC’s print media department. He also served a stint as Treasurer of the Society of Illustrators, during which he created significant work for the United States Air Force Art Program.

Terry also worked at some of the top agencies of the ‘50s and ‘60s, including Stephens Biondi deCicco, Diener/Hauser/Bates, and Group West Studios alongside top-notch illustrators Ren Wicks and Art Center instructor Joe Henninger.

In part, it was his Art Center network that provided him jobs. “I had a lot of Caucasian friends with whom I got along with quite well. There have always been some people that have never had that racial bias or that racial hostility. They accepted people for who they were. When they got into positions at studios or companies, they gave me the work I wouldn’t get otherwise.”

At the same time, Terry started what would become a successful freelance career. “I was freelancing all the time,” he said. “Technical illustrations, exploded drawings, production design, book covers, small paintings. When you’re out there hustling, you take what you can get and you make the best of it. Eventually, through my freelance work, I was able to get better employment opportunities. When I look back, I did a lot of extraordinary things.”

Terry’s enthusiasm for learning is still strong. “All this new technology is fantastic. A few years ago, I signed up for computer classes at Glendale Community College. I’m learning how to build websites and eventually want to start drawing and painting on the computer. I’m just sorry I didn’t get into it sooner.”

While still learning, Terry already has a couple of websites under his belt: a portfolio site he continues to update with previous and current work; and a site dedicated to the history of African Cowboys, which features his own art prints and reproductions about notable African-American men and women of the Old West.

In addition to his interest in history and websites, he works with his daughter Sharon Terry, who also attended Art Center, on a line of greeting cards. “When I see a student that has talent, or the possibility of talent, including both of my daughters, I tell them to learn to draw. Once they learn to draw, they can concern themselves with the bigger questions about where they want to study or what type of job they want after college.

“Sharon got a scholarship to attend Art Center’s Saturday High program, and that was really the beginning of her career. That type of access—access to classes and quality instruction—is the best thing for students today.”

And Terry is particularly proud that both his daughters have successful careers in art and design. “I was able to guide both of my daughters through some of the doors that I had to break down on my way up. Of course, I didn’t realize I was breaking down doors at the time. I just wanted to find a job as an artist.”

I wonder of McKinley Thompson was the first African-American graduate in Transportation Design. I just missed him when I entered Art Center in Fall ’54; I believe he graduated in Spring ’54. I crossed met him at Ford during the early ’60s.

Could someone confirm whether he was the first African-American graduate? If possible, I’d like to be in touch with him regarding a book I am writing.

Thanks,

Del Coates

Fabulous! Very inspirational. The kind of message every young African American needs to immerse themselves in. This isn’t to say everyone can’t benefit from this story BUT too many of my folk allow their children to whine about not being accepted. This story, like so many others focusing on successful people, makes it clear that racism isn’t the draw-back.

Thanks Mr. Terry to have seemingly shunned the “leadership light” in our famous city of Pasadena and instead walked the walk while avoiding talking the talk that so many Pasadena African Americans spend their time doing.

!