Art Center librarian Simone Fujita and Illustration student Kristina Halcromb discuss children’s books by African-American illustrators. Art Center photo by Sylvia Sukop

“You get a feeling of music. Totally music. Rhythm,” Kristina Halcromb muses out loud as she runs her fingers over Duke Ellington’s blazer, rendered in rich hues of purple, pink, blue and brown in a children’s book she is encountering for the first time. Emanating from the trombone pressed to the jazz musician’s lips, clouds of sound swirl across the page.

“The hand drawing makes it more appreciative,” says the Illustration major, in her final year at Art Center College of Design.

Duke Ellington: The Piano Prince and His Orchestra is among a dozen books arrayed before her on a wooden table in the college’s James Lemont Fogg Memorial Library, culled from its growing collection of children’s books by African-American illustrators. Most of the books Halcromb has never seen before. Even the few that she is familiar with—like Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters, based on an African folktale, and Please Baby Please, coauthored by Spike Lee—she discovered as an adult, when she became a teacher’s aid at Pasadena’s Cleveland Elementary School in 2009.

“Lots of mixed-race children go to school there,” she says, “and the teachers have an amazing library.”

Halcromb admires Brian Pinkney’s illustrations in Duke Ellington: The Piano Prince and His Orchestra.

Exploring Art Center’s collection brings fresh surprises and Halcromb finds herself wishing she’d had access to books like these when she was a child. “I didn’t know there were so many,” she marvels.

Spotting one of the few books from her childhood that she remembers being able to identify with—Corn Rows, illustrated by Carole Byard—she lights up. “When I found a book about someone with hair like mine, I thought ‘Yay!’ Up until then my mom did perms in my hair to straighten it. This book was helpful to let me embrace it.”

The kinds of images that children are (or are not) exposed to have profound and well-documented impact on their self-image and self-esteem.

Halcromb, a member of Chroma, a multicultural student organization at Art Center, quickly sums up the limited range of stories available about her heritage. “There’s slavery. There’s the Harlem Renaissance. There’s jazz. Then it just cuts off. Everything else is European-based.”

Art Center librarian Simone Fujita, sitting at the table with Halcromb, nods her head in recognition. In her master’s thesis Fujita explored ways in which libraries might support multiracial children’s identity development through the thoughtful use of children’s literature and improved cataloging efforts.

“Demographically, multiracial children comprise one of the fastest growing youth groups in the U.S.,” Fujita explains, “yet there is very little visibility and representation in libraries. So my thesis advocated for greater access to children’s books that do provide depictions of mixed race children and families.”

Fujita and Halcromb agree that children’s books featuring people of color tend to focus on traditional folktales, holidays such as Kwanzaa, or historical subjects—including slavery.

“I’m tired of associating myself with the history of slavery,” Halcromb says flatly. As a writer and illustrator of stories herself, she is far more interested in what came before that. “I’m trying to push it way back,” she says with a sweep of her arm, back to a time before Europe’s reach extended to other continents.

By way of example she describes a recent class assignment: to illustrate The Little Prince.

“I read the book. I didn’t like it. I thought it was boring, dull.” So she asked herself, “How can I twist this?”

With the teacher’s permission Halcromb scrapped the original assignment and wrote an entirely new story of her own—set in Polynesia. The main character: “A koala bear who feels left out in his world. He carves out a canoe and leaves on an adventure. He visits different islands, encounters different gods—the god of water, the god of wind—and along the way he gets younger and younger till he’s a child again.”

Even Halcromb isn’t sure how the story will end. She’s still researching (oceanography among other topics) and writing it.

Halcromb grew up in San Bernardino, a place she describes as “boxed in by freeways,” with a growing divide “between rich and poor, Caucasians and people of color.” Art became her way out.

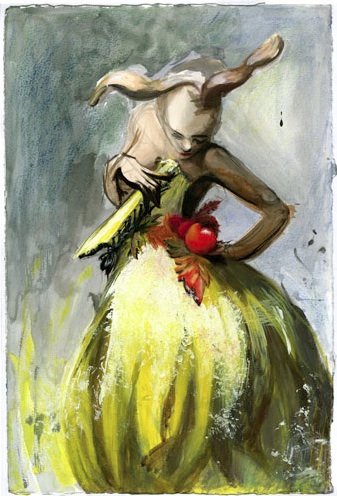

A painting by Kristina Halcromb, courtesy of the artist. © 2012 Kristina Halcromb.

At the age of four, she recalls, “I first saw Rugrats on Nickelodeon and I started drawing—everywhere, all the time.” Her mother, recognizing Halcromb’s talent, sought out books and art classes for her in the community, since such resources simply weren’t offered in her public school. Instead, Halcromb’s early artistic training took place at a local senior center. And Norman Rockwell was one of her favorite illustrators.

Fujita reaches across the table and hands Halcromb a book, Black Authors and Illustrators of Books for Children and Young Adults: A Biographical Dictionary

“Wow, it’s really thick,” says Halcromb, astonished to be holding the biographies of 274 authors and artists largely unknown to her. The book was published in 1998, when Halcromb was in middle school, dreaming of becoming an animator.

As a student at Art Center Halcromb has not only refined her drawing skills but also developed a critical eye. “When I was young we were saturated with Disney and the way it looks, the clean lines and bright colors. When girls went to the library they all wanted the princess books.”

In her own work (view examples on her blog, Karisma) she’s been exploring a variety of media and visual styles, mostly hand drawn, while developing highly original characters of her own. None are princesses—though in the future she does not rule out “exploring royalty in other nations.”

Halcromb’s fiancé, Art Center alum Donivan W. Howard ILL 97, is an artist and illustrator living in Atlanta, Ga. Visiting him there, she says, it can feel like a different world. “I see so many books with people of color, even out in the suburbs!”

Halcromb will join Howard in Atlanta after her graduation in August, and they’re planning a wedding this fall.

In terms of career ambitions, “I still have a heart for Nickelodeon,” she says, momentarily wistful. “But I want to start my own company. I want to create my own stories and characters, do graphic novels, and children’s books, and toys. I love the big screen too, and 3D, which is opening up whole new avenues for how things can look.”

Opening up whole new avenues for how things can look. It’s an idea that also inspires Fujita. “In Art Center’s library we want to embrace a wide array of viewpoints and voices, reflecting our student body in all its diversity. Everyone benefits from that.”

—Sylvia Sukop

Pingback: For Art Center at Night director Dana L.Walker, “Diversity is really about all of us.” « Dotted Line | Official Blog of Art Center College of Design | Pasadena, CA | Learn to Create. Influence Change.