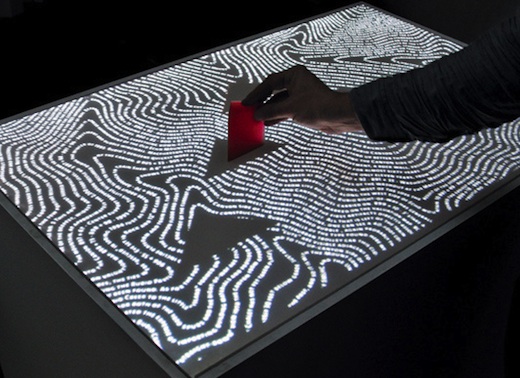

Paul Hoppe’s installation “ECHO: The Fragility of Moments Suspended in Time.”

It’s the final week of the Fall 2012 term and “The Annex”—a nondescript temporary building on the northern end of Art Center’s Hillside Campus—is doing a good job hiding the feats of alchemy occurring within its walls.

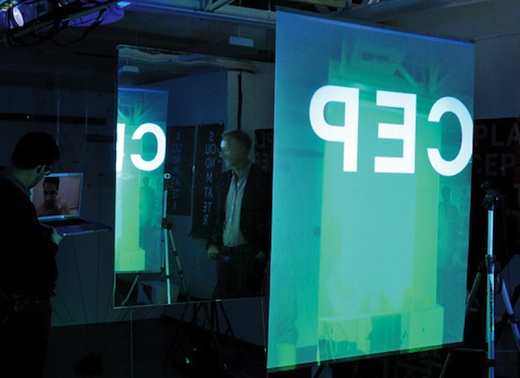

Entering classroom A7 on the second floor of this battleship grey structure feels like stepping into Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. In one corner, a student waves his hands to stir into motion a field of floating green particles. In another, students walk through a mirrored passageway that reflects their position in time and space from exactly 10 seconds ago. Elsewhere, two ellipses face one another—one on the floor, the other on the ceiling—as they project images of nature, architecture and words like “renewal” and “emergence.”

What is going on here? These upper-term Graphic Design students are tweaking final projects they created for Advanced Graphic Studio, a class that’s part of an ambitious undergraduate curriculum called transmedia within the Graphic Design Department.

Ka Kit Cheong’s installation “Plaception — Phenomena of Perception in Place.”

“The trans part of transmedia is that the designer transforms and transcends media categories, and by so doing, creates new media categories,” says Nik Hafermaas, chair since 2004 of the Graphic Design Department, who taught the department’s first transmedia course four years ago.

Transmedia is an experimental curriculum that razes traditional barriers separating designer, artist and curator. It entails working across both emerging and traditional media—everything from data visualization to spatial experiences—to create an emotionally resonant message. It’s a field in which Art Center is leading the charge, and an ambitious endeavor whose potential is being fulfilled in its students’ work.

Pushing the medium

“This particular class is one of the hardest-working I’ve had in my 13 years of teaching,” says Transmedia Design Director Brad Bartlett, who has cultivated the Graphic Design Department’s transmedia curriculum since it first launched. “We’re forcing them to work outside their comfort zone, and in the process they’re discovering new things about themselves and the medium they’re trying to push.”

Pushing a medium to its limits is nothing new to Bartlett. A multidisciplinary designer whose firm won a 2012 prize for Excellence in Publication Design from the American Association of Museums, Bartlett has explored the relationship between media and culture since the mid-1990s, when his projection-based graduate work from Cranbrook Academy of Art was presented at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). And Art Center’s transdisciplinary synergy has been a good fit for Bartlett, who has also taught Transmedia Design in the College’s Graduate Media Design program—a course created by that department’s chair Anne Burdick.

Graphic Design instructors discuss student Geoffrey Brewerton’s work. (L-R) Brad Bartlett, Brewerton, Sean Adams, Nik Hafermaas.

In Bartlett’s Advanced Graphic Studio, students select a well-known or compelling subject of interest (say, a particular artist or site of historical significance) and tackle it from multiple angles—a book, a series of posters and a spatial interactive experience—in order to tell a powerful story that uses the attributes of each medium to their full potential.

“Transmedia is about reacting to and anticipating the technological and social changes affecting how we interact with one another,” says Bartlett, who asks his students to project five to 20 years into the future. “We’re looking at not just how content and visual language can flow from one medium to another, but also how new media can emerge.”

For Cindy Mai, who came to Art Center in 2010 with a bachelor’s degree in political science from UCLA, transmedia boils down to making a compelling argument and then discovering the best way to present it. “I start with a huge amount of information, pare it down to its most potent parts and create a system of graphics,” says Mai of her process. “But then the challenge is to figure out where that system can live. With transmedia, it can live beyond traditional limitations of printed matter or a digital screen.”

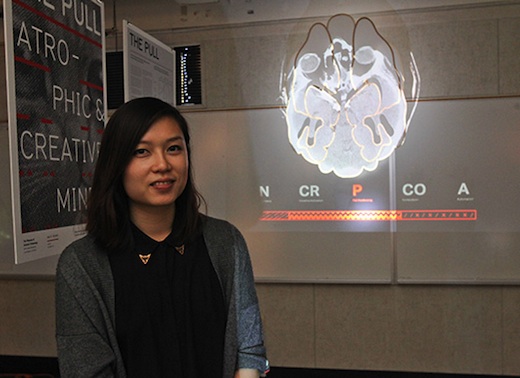

Cindy Mai with her installation “The Pull: Atrophic and Creative Minds.”

Mai used Bartlett’s class as an opportunity to explore the links between creativity and frontotemporal dementia a disorder that affects the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Her project The Pull: Atrophic and Creative Minds, began with an interest in English artist Louis Wain (1860–1939), whose illustrations of wide-eyed cats became increasingly abstract as his brain deteriorated. “He obsessively painted cats his entire life but his disease made his work really interesting,” says Mai. “I was fascinated by that give-and-take relationship.”

Mai envisioned The Pull as an exhibition at Culver City’s Museum of Jurassic Technology, and created an exhibition catalog that introduced Wain and the disease and whose structure mirrored the onset of the dementia. For the spatial interactive element, Mai fashioned a series of brain slices out of plywood frames and sheets of mylar and hung them from the ceiling. Then, using the Processing programming language and a motion-detecting Microsoft Kinect peripheral, she projected MRI images of different stages of brain deterioration onto the slices, which changed based on the viewer’s proximity to the installation.

“I hadn’t programmed before, so I wanted the interactivity to be simple,” says Mai. “If I were a master at coding I could have included so much more information.”

Data, emotion and memory

But becoming a master coder is not the goal here, says Hafermaas. “We want our students to design experiences that serve a purpose, so we encourage them to use unfamiliar media and to engage in open-ended experimentation.”

UEBERSEE’s “airFIELD” at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. Photo: UEBERSEE

To see experimentation-with-purpose in action, just step inside the International Terminal at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. There, in the center of the world’s busiest travel hub, you’ll find transmedia design firm UEBERSEE’s airFIELD, a dynamic sculpture 90 feet in length. Made of thousands of suspended liquid crystal discs that change from opaque to transparent in wave-like patterns based on live Atlanta flight traffic, the sculpture was designed by Hafermaas, founder of UEBERSEE, along with Art Center alumni Jamie Barlow ENVL 05 and Dan Goods GRPK 02.

“You can just marvel in its beauty, but there’s also a display nearby that explains what you’re looking at,” says Hafermaas. “So it’s data visualization that functions on an emotional level.”

Student Paul Hoppe arrived at Art Center in 2009 from Azusa Pacific University, where he double-majored in fine art and graphic design. He came to the College to focus intensely on graphic design, but the more time he spent in the classroom, the more he found himself returning to his media-based installation roots. And it paid off. In late 2011, he won an Adobe Design Achievement Award for Exploratorium: Generative Identity, an algorithmically generated typographical identity he created for San Francisco’s Exploratorium museum as a project in Bartlett’s Type 4 class.

Paul Hoppe puts finishing touches on his installation before a final critique.

Now, one year later in instructor Miles Mazzie’s MediaTecture course, Hoppe is accessing a visual database using an interface that looks like it was beamed down from the starship Enterprise. As he moves a red resin triangular prism atop a table, he activates different chapters on the rise and fall of a popular turn-of-the-century Pasadena tourist attraction atop Echo Mountain, which came to be known as the “White City.” Destroyed by a series of fires, the resort comes back to life through sounds and via projections on the table and on an upside-down papier-mâché mountain suspended above the table.

Echo Mountain, just six miles from Art Center’s Hillside Campus, and the scenic mountain railway line that took visitors there were the brainchild of Thaddeus S.C. Lowe, a self-made scientist, inventor and Civil War aeronaut turned millionaire entrepreneur. “Lowe put his life, fortune and everything into this project, but now all that exists are the ruins,” says Hoppe. “I wanted to draw a correlation between the remaining artifacts and the history of the place, as well as explore how memory works, both historically and neurologically.”

Hoppe imagined this installation—ECHO: The Fragility of Moments Suspended in Time, which he co-developed in Bartlett’s Advanced Graphic Studio course—as the centerpiece of an exhibition co-presented by the Pasadena Museum of History and the UCLA Department of Neurology. And while scanning historical images for his project, a glitch affirmed he was on the right track. “One of the scanners at the library had a loose connection, and was creating weird distorted versions of the images,” he says. “And then it clicked. I thought, Oh, that’s how our brain works!”

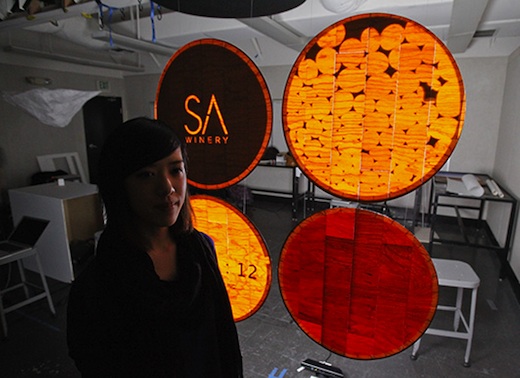

Charlene Chen with her proposed transmedia rebranding for San Antonio Winery.

A curriculum distilled over time

Last December, Petrula Vrontikis, an instructor in the Graphic Design Department who teaches advanced-level studio and career preparation courses, presented her current academic research at AIGA’s Design Educators Conference. In her paper titled “Transmedia Design: Crossing Boundaries for a New Kind of Graphic Design Practice,” she argued that graphic design education was coming “face to face with its irrelevance” and that adopting “an integrative practice that crosses all media” and that fosters “cognitive ambidexterity” is necessary to keep up with a field undergoing rapid change—the exact kind of practice occurring today at Art Center.

But, Vrontikis cautions, transmedia is not something that can be simply implanted into a program’s curriculum. “The reason it’s working so well here is that its roots were being developed years ago,” says Vrontikis, who attributes Hafermaas’ background in environmental graphics and spaces and his appointment of faculty directors in areas such as motion design and interaction—areas which had not existed within Graphic Design until recently.

So now, when a student like Charlene Chen—whose fourth-term MediaTecture project imagined how Los Angeles’ San Antonio Winery could transform its brand experience by adding animated and context-sensitive distillation data to its wine bottles and barrels—arrives at the College, she has all the necessary resources to help her excel in a burgeoning field.

“Everything is in place for Charlene to take courses ranging from interaction to motion, print to packaging, letterpress to transmedia, and all taught by people who are top-notch in their fields,” says Vrontikis, who then proudly adds, “Other than right here, that doesn’t exist.”

For an even deeper interactive dive into the world of transmedia, check out the full Dot Magazine story here.