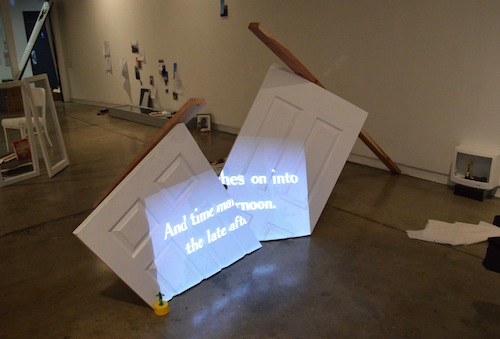

This creative manifesto is part of a series of first-person pieces by Fine Art students reflecting on the ideas informing their work. Each post will feature the artist whose work is currently rotating through the Undergraduate Fine Art Student Gallery, at the Hillside Campus. This week, student Kristy Lovich explores the sources of inspiration behind her intimate and evocative installation entitled, “Don’t go runnin off, there’s lots of shit to carry!”

We are building a house that remembers.

Don’t go runnin’ off, there’s lots of shit to carry!

This Place: and we have so much to do; so many things to look at.

When I was a kid, my mom would ask me to clean my room, the room I shared with my sisters. And because we were always making things, because I was always building something and taking something apart, the room was always a mess. Always in each corner was the evidence of the simultaneous destruction and construction of the small worlds I occupied: the theater, the miniature, the fantastic, the hidden, the movie, the book, the magic. Collections piled onto collections. And alongside these precious worlds were also the objects of this world: the dirty laundry, the trash, the long abandoned can of soda, lollipop stuck to its own paper, a forgotten homework assignment. On that dreaded Saturday morning, when she had finally tired of negotiating the path carved into the sea of things in our room, my mother would tell us that we were not to emerge until it was clean. Until everything was in its place.

What she didn’t know, what I found so devastating, was that for me, everything was in its place! These spaces were all of their own, suspended in their distinct progress toward their own creation. Installations, micro worlds, each one designate from the other but always intertwined in some way with one another. I would read a chunk of a book which would tell me what was next in line to change the play, which would tell me then how to go about finishing a drawing, and so on. Often, in these spiraling zones of creativity I would lose track of this world, forgetting to eat, to throw out my soda can, to do my homework. Time became malleable, often abandoned. I was never sure what came first or last. But despite my forgetting, this world kept on unfolding too. With my mother’s request, I would become anchored again in this world, the real world, and I would submit to the task of organizing the place which was both an escape from what we might think of as reality and the vehicle through which we are able to evade the confines of the allegedly real, the way to remake this world: the vehicle into the imaginary.

I remember you. I am asking you to remember too.

One of the great things about cleaning my room was that I was able to rediscover things. Before I put away an object, made the decision to keep it or throw it out, found the perfect spot for it to live, I was able to look at it, remember when I acquired it, go back into the moment in which I encountered its being. When its being came into contact with mine. Immediately, through holding it, touching it, I was able to travel to that distinct moment and conjure up the story of its becoming, the way it marked a certain spot in my becoming. Because I had chosen the thing, its meaning was encased in my intention to protect it or if the circumstance presented itself, to throw it away. Either way, the objects had the power to provoke a consideration. To forget or to remember a story.

And sometimes, amidst the remembering of a beloved story there was also the remembering of a heartache, a fissure. I might pick up the glass horse that tragically fell, breaking its leg clean off its body. Or the music box that was crushed in the move, no longer able to play a tune. Or the videocassette tape whose moving images were nearly indecipherable, but which contained the only evidence of your family outings, so you kept them anyway. The piles of broken things, the parts of what had been, became important. I was encouraged to throw these things out but refused. I thought it was important to remember the moments when things fell apart.

Looking back, it is easy to see why I place so much importance on remembering, even now as an adult. The remembering helps protect the cord, to light the path down which you came. It is equally our devastations that make us, as it is our joys. And maybe, the best way to form the liberation from this harm is to keep its remains in plain sight, transparent, where they are at least honest, where you can determine how you will change them and you cease their ability to continue changing you without your consent.

Don’t go runnin’ off, there’s lots of shit to carry!

Though I would put up a good fight against cleaning my room, I would arrive to my eventual participation because alongside my chore, my mother was working on the rest of the house too. Rearranging, putting things away, polishing the glass, vacuuming. And my sisters, each with their own tasks were contributing. This is what made Saturdays fun, even if they were filled with work: everyone was helping to clean the house. My mom would make sure of this at every turn, that we were all doing our part. Without fail, each time we returned home from the grocery store or the laundromat, she would say as she parked the car: “Don’t go runnin’ off, there’s lots of shit to carry!” And we would still our escape from the vehicle and each grab a bag to ferry into our home. She made sure we each knew we were a part of a family, that as long as we were together we would be able to make things work, even when things were hard. Our mutual labors adhered our relationship and guaranteed our survival.

The Middle: Opening the Door

Many years later, I stumbled into a desire to understand how some people, when given the choice not to, feel compelled to participate in the act of changing the world. Of course, I realize the breadth of that phrase. To change the world can mean so many things. However, in this moment that we are sharing, the decision to do so is charged and defined by our present circumstances. And further, it is distinct to each of our own personal experiences. I began to reflect on this process in my own life, reaching for those specific moments in which my understanding of who I am, how I am in this world was impacted by a distinct event: something happened to me; I bore witness to something happening to another. And I wondered what these two vantage points did, as they came together, to construct an aptitude for empathy: A way to see my life intertwined with another’s, a way toward solidarity, a way to love.

I thought of these stories, each of them shaped by their own objects, images, characters, events, architectures, and rhythms like they were those distinct spaces in my room as a child. That the interior home in which they sat created a landscape, composed like a constellation in which some things stood out as important while others fell away: Charlie Chaplin, Dorothy Gale, the broken passenger side door of a 1978 Ford Fairmont, circus peanuts, the Hollywood wax museum, my old sneakers, the day room in ward 9, an assault on my body, my own institutionalization. That these things are framed further by the events of the exterior, the political: the beating of Rodney King, the Los Angeles uprising of 1992 (sometimes called riots), the war in Iraq, police brutality, the murder of Trayvon Martin …and so many more.

And as I carried out the work of reconstructing the lineage of my own consciousness it became clear that I needed to reach for yours too. To ask you to meet me in the middle. To tell me your story. So that maybe, in that encounter we might be able to compose an archive, build a strategy for cleaning this room, for building this house.

Then, maybe our new love won’t leave any evidence. It’ll all be locked up tight, swimming in the liberation of memory —and I’ll have to sit facing you, trying to form enough coherent sentences for you to believe that you know what happened.

A New Place

Despite my complaints about dismantling my creations, putting away my things, once I finished cleaning my room I was always so excited. The now clear floor, clean shelves meant that there was room to build something new. To make a new mess. To imagine another world inside the world of our house. The clearing of the space was an invitation into possibility. And this new place, more invitation than imposition, might become an opportunity, between you and I, to build a house that remembers.

So, don’t go runnin’ off, there’s lots of shit to carry!

![klovich2[1]](http://blogs.artcenter.edu/dottedline/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/klovich21.jpg)