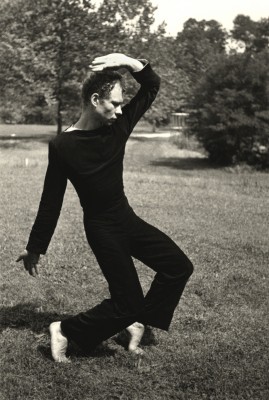

Photo: Hazel Larsen Archer, Merce Cunningham Dancing, c. 1952-53, gelatin silver print, 8 ¾ x 5 7/8 inches. Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center.

“Most people in the room probably know a little something about Black Mountain College, and it’s probably part wrong and part true,” said Helen Molesworth. Relaxed in black sneakers and a loose sweater, the new chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, less than five months into her new job, offered a candid and engaging behind-the-scenes look at her work on a revealing new exhibition about Black Mountain College—the first comprehensive exhibition on the subject to take place in the United States.

The curator’s talk in February, a full year ahead of the exhibition’s opening in L.A., was part of both the Wind Tunnel Lecture Series and Art Center Dialogues. And as she disclosed to her unsuspecting audience at the outset, “You’re the first! I haven’t actually given a Black Mountain talk yet.”

For Molesworth, Black Mountain College’s mythic status—as the birthplace of the neo-avant-garde and the site of legendary collaborations by Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage and Merce Cunningham—has in fact been a problem to overcome, an impediment to a more complete understanding of its history. “It was a place charged in ways that engendered mythmaking from its inception,” she said, “and a lot of that mythmaking was self-generated.”

Years in the making, the exhibition Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957, aims to get beyond the mythology and closer to the actual lived history and art produced there. Accompanied by a prodigious 400-page monograph from Yale University Press and featuring individual works by more than 50 artists, the show will debut in October at the The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, where Molesworth served as chief curator before making a transcontinental leap of her own. It travels early next year to the Hammer Museum for its Los Angeles presentation February 21–May 15, 2016.

Ruth Asawa, Dancers, c. 1948, oil on blotting paper 12 x 19 inches. Weverka Family Collection. © Estate of Ruth Asawa. Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

The idea for Leap Before You Look grew out of Molesworth’s work on an earlier exhibition about the relationship between dance and drawing. It was her discovery of a California artist that sent her spinning. “I had this really great funky assistant from the Bay Area who asked me if I had ever heard of Ruth Asawa and I had not—and I immediately fell in love with the work,” Molesworth recalled. “A lot of folks out here knew who she was, in a way that people in New York, where I’m from—the capital of the 20th century,” she said pointedly, eliciting chuckles from the audience, “did not know who she was. I learned that she had gone to Black Mountain College, and I realized at that moment that I didn’t know anything about Black Mountain College. All of a sudden the story that I was carrying around with me seemed really small.”

To uncover the larger story, Molesworth immersed herself in the archives of the College and the maverick artists associated with it. “I wanted to see if it was possible to make an exhibition about an art school,” she said.

Black Mountain College, founded in 1933 by progressive educator John A. Rice and inspired by John Dewey’s principles of learning by doing, was located in the small, rural town of Black Mountain, 10 miles outside of Asheville, in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. When he was fired from a tenured faculty position at a conservative college in Florida for his radical ideas, Rice was encouraged by colleagues and students to start a new school. Although Rice was not an artist and didn’t know any artists, he wanted to create a liberal arts college that placed art at the center of its curriculum rather than at the periphery—all of the arts, from poetry, music, dance and theater, to visual arts, textiles, jewelry making, book binding and more.

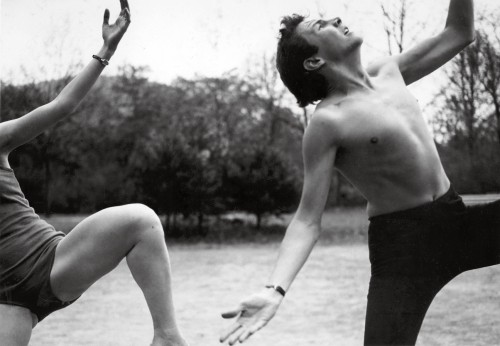

Photo: Hazel Larsen Archer, Elizabeth Schmitt Jennerjahn and Robert Rauschenberg, c. 1952, gelatin silver print, 6 1/4 x 9 ¼ inches. Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center.

In addition to upending the usual educational priorities, the school would also blur the boundaries between work and play, and between teacher and student. “One of the tenets of progressive education was to profoundly challenge the hierarchical distinction between student and teacher,” said Molesworth, “and to create an environment in which all were learning.”

With the help of supportive friends and colleagues, resources were marshaled—“one guy goes out and gets money, another guy goes out and gets land,” Molesworth recapped—but still they had no artists.

Events unfolding in Europe would prove decisive. In Berlin in 1933, the famed Bauhaus school was shut down under Nazi pressure. Josef Albers, who had taught there since 1923, was invited along with his wife, the artist Anni Albers, to join the faculty at Black Mountain College. They accepted and, despite their lack of English, together became the pedagogical engine of the school.

“Albers brings with him the three central classes he developed as the core arts curriculum at the Bauhaus—a class in drawing, a class in color theory and a class in materials studies,” said Molesworth. Pioneering in its day, this foundational curriculum has become standard at many art schools including Art Center College of Design.

Helen Molesworth points out Elaine de Kooning working on a Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome in a 1948 photograph taken at Black Mountain College.

Molesworth went on to describe the extraordinary range of art and artists that emerged from Black Mountain College, their relationships and mutual influences. At one point she stepped from behind the podium to draw attention to one particularly remarkable photograph: Elaine de Kooning working on Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome.

Such exciting art historical finds notwithstanding, perhaps the richest discovery for Molesworth lies in the powerful democratic ideal at the heart of this radical experiment in arts education.

“Many of the instructors consciously didn’t want the students to think of themselves as artists,” said Molesworth. “They wanted students to learn how to solve problems so that they would learn to think critically. And in thinking critically they would become aware of the necessity of making choices. And in making critical choices they would be better equipped to be democratic citizens. The ideal was that students would become more ethically minded, more aware of the kinds of choices that one has to make every day.”

This is the period between 1933 and 1945, she reminded her audience—yet such educational aims seem no less relevant today. “The capacity to make a critical choice was at the very root of the democratic process.”

–

The Wind Tunnel Lecture Series on the critical study of art and design is part of the Graduate Art Department’s Graduate Center for Critical Practice Initiative, and presented in collaboration with Media Design Practices. Helen Molesworth’s lecture was also part of the Art Center Dialogue series, made possible by Toyota Motor Corporation; and in collaboration with the gallery Hauser Wirth & Schimmel. Videos of the 2014–15 Grad Art lectures, including Molesworth’s, can be viewed here.

After a failed attempt the previous year, Buckminster Fuller’s first geodesic dome was successfully erected in the summer of 1949 at Black Mountain College. Photo: Hazel Larsen Archer, Buckminster Fuller Inside His Geodesic Dome, 1949, gelatin silver print, 9 ½ x 9 ¼ inches. Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center.