Before James Dyson first mesmerized TV viewers with his early demonstrations of his sleekly designed and innovatively engineered vacuum cleaner, capable of coaxing the dirt from off any surface, home cleaning devices were many things but sexy wasn’t one of them. But after Dyson’s invention captured the popular imagination (not to mention a landfill’s worth of grit and grime) and became the industry standard for home suction, consumers’ perceptions (and expectations) of vacuums were forever altered, in terms of both performance and prettiness.

Though such paradigm shifting innovations are dependent upon a mysterious combination of luck, timing, research and inspiration. The Dyson company has continued to expand upon its success by upholding its high standards for innovative design and engineering. Cultivating the next generation of design innovators is another vital part of the company’s forward-thinking ethos. To that end, the James Dyson Foundation has been rewarding ground-breaking feats of creative engineering with the James Dyson Award, created in 2002, which offers a $45,000 prize to a design that “solves a problem.”

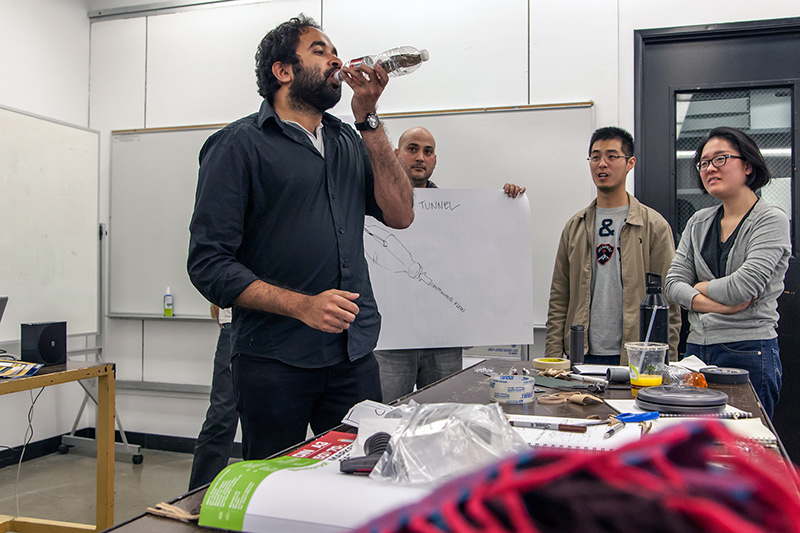

The foundation has recently started seeding the field by conducting design engineering workshops with K-12 students in Chicago. Last week that strategy graduated to the college level, when a team of Dyson engineers lead Art Center students from three departments — Transportation, Product Design and Graduate Industrial Design — in an exercise testing their teamwork, problem-solving, creativity and craftsmanship.

The challenge couldn’t have been simpler. But it was far from easy. Design engineers Rob Green and Sean Hopkins challenged five teams of students to conceive and create a product that solves a problem in one of five categories: health, sustainability, sports, lifestyle and education. Time allotted: One hour.

A class of early-term Transportation students tackled the assignment in the morning. Each group quickly began sketching out ideas on the butcher paper laid out on tables around the room. The sports group immediately trained its focus to products that might create greater mobility for those suffering from sports-related injuries. The education crew batted around ideas for apps to help students with organization and homework. While the sustainability group became a model for collaboration as each of its four members contributed simultaneously to a sketch for harnessing wind power. The lifestyle group laid out models for a gleaming chrome product. While the health group began constructing its prototype out of cardboard almost immediately.

About half-way into the prototyping session, one of the students approached one of the Dyson design engineers holding a Lazy Susan he’d found laying around the classroom and asked, “Is this legal?” No, it wasn’t. All groups were required to stick to the materials they were given: cardboard, plastic tubing (hey, it was Dyson, after all), plastic wheels, scrap metal and hot glue. Still, that student’s spirit of scrappy ingenuity earned him some major cred with the Dyson team. “These guys are so impressive, it’s ridiculous,” marveled the engineer after the student returned to his group.

By the hour’s end, each of the teams was poised to meet the deadline, even as students hurriedly scrambled to add finishing touches, not unlike chefs adding garnishes to their plates in the final seconds of an “Iron Chef” challenge. The first group to present its product revealed a portable water purifier it had made for the health category. This was no ordinary Brita pitcher, however. This cardboard creation featured hand pumps, wheels and tubing for extra purification. And the room broke out in ooh’s and aah’s when the team opened the lid to reveal an intricate series of nesting filters.

Next up was the lifestyle group, which demonstrated its hand-held dog groomer, with a vacuum suction feature designed to eliminate furball cleanup. Even though the Dyson team insisted that there was no mandate to create vacuum-related products. The lifestyle group charged ahead with its concept and finished with a gleaming chrome device with a retro appeal.

The sports group dubbed its orthopedic accessory the Wrist Chariot. And its design, featuring a flat bed for the wrist and large wheels near the elbow for mobility, did vaguely allude to Spartan transportation. The splint was tricked out with a light source at the bottom for reading and finding lost keys in the dark.

The environment group built a portable blimp, designed to attach to any structure to harness wind energy. The blimp generates electricity using wind turbines and funnels the energy to its destination through a power cord. The prototype, constructed of out of cardboard and duct tape, displays the design’s portability and scalability — it can be used for anything from a camping trip to providing backup power for a school.

Finally, the portable school supply carrying unit, designed by the education group, revealed the class’ transportation roots. The prototype resembled a motorized palate which would meet students at their cars and deliver their heavy books and art supplies to their classrooms using a GPS tracking system.

The Dyson team was so impressed, one mentioned offhandedly that any of these designs would be a strong contender for the James Dyson Award. And this was just the first group of the day. Later classes would dream up another five contraptions and take apart Dyson’s brainchild (aka the world’s sexiest vacuum cleaner). Just imagine what these students might achieve by the application deadline in August.

After returning back east to the winter chill, the Dyson team wrote “We were literally blown away by the reception we received – by the students, the faculty and even the President. The Foundation’s partnership with the Art Center is well on its way and I cannot wait to see all of those seeds planted yesterday start to grow.”