“We began as artist and dealer, but it developed into the most important personal relationship I made in my 16 years in the field,” says Chicago gallery director Paul Berlanga of his friend, Art Center alumnus Wayne Forest Miller (Photography ’41). They met in 2001, at an exhibition of Miller’s work at Northwestern University’s Mary and Leigh Block Gallery. “After a momentary glance at his work on the walls [the Bronzeville series], I knew the Stephen Daiter Gallery needed to represent this man.” Miller, a Chicago native, was 82 years old at the time, with a long and legendary career behind him — World War II photographer in Edward Steichen’s elite U.S. Navy Combat Photo Unit, member of Magnum Photos, and recipient of two consecutive Guggenheim Fellowships for his landmark project documenting the African American community on Chicago’s South Side in the late 1940s. Miller, who lived in the Bay Area with his wife of 70 years, passed away on May 22, 2013. Berlanga gave a eulogy at the California memorial service last fall, and now shares his memories of the photographer — “Wayne always preferred ‘working photographer’ to artist” — with Dotted Line.

As a dealer, I have often introduced collectors to the work of Wayne Miller by saying, “Here is the most important photographer you’ve never heard of.”

That was Wayne’s “fault.” That was Wayne’s way. He had never pursued publicity or a career in the gallery or museum world. Eventually that world pursued him.

Picture this. It is 1942. Wayne is age 22, learning on the fly, as he stepped into World War II on the decks of the Saratoga aircraft carrier. His job was to document the lives of the Navy enlisted men in whatever way would help win the war. His only formal schooling in photography had been basic classes the year before at Art Center, and he always appreciated the grounding he received there not only in printing, but in realizing the nearly unlimited possibilities inherent in the medium. He also lacked any real military training. Nonetheless, he spent the next four years risking his life documenting the gamut of human emotions in the face of deprivation, destruction and death. Along the way he happened to create an amazing body of work — beautifully crafted — that expressed the everyday humanity behind the faces of soldiers and civilians and innocent children, all caught up in the largest conflagration in our history.

Flash forward. California, 1979. It is drizzling and Wayne is lying on his stomach upon some foraged sheets of damp cardboard in a rain-soaked backyard, filled with mud. He is making an eye-level portrait of a blue ribbon-winning Shar-Pei, a dog breed still exotic in the United States. He is on assignment for People magazine. “Why is a grown man doing this, I began to wonder,” he said later. On top of that he felt that he had made no good exposures. Miller dutifully shipped off the prints which were published in the Paris edition of People. The joke was on Wayne. The cable that came back from Paris read, “…this is the most popular story we’ve ever run.”

“Which taught me something about the French,” said a bemused Wayne, who cited that shoot as the beginning of him eventually turning his attentions away from photography. He had done it all. The rest of his life would be devoted to environmental education, land management reform (read politics), forestry and his family.

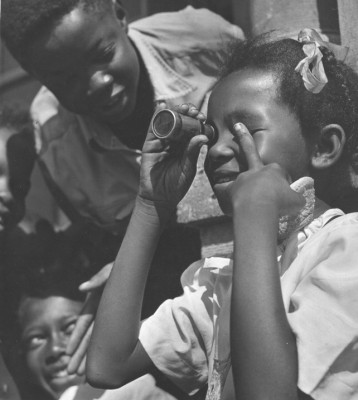

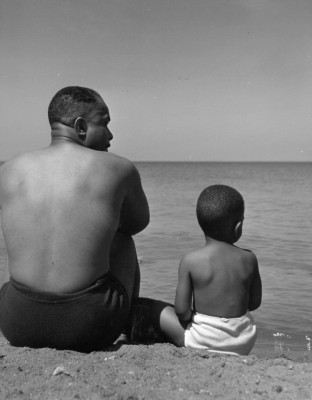

Between the World War and the Shar-Pei lay a monumental mid-century career in photography. It included “The Way of Life of the Northern Negro,” later published as Chicago’s South Side, the most beautiful and balanced photographic overview of the lives of African-Americans in postwar urban culture ever created. [Editor’s note: When the University of California Press book came out in 2000, the Chicago Tribune hailed it as “A long-overdue contribution to the photographic literature of the period known as the Great Migration.” And the New York Times Book Review observed, “Miller’s work is intimate but never presumptuous.”]

Wayne’s career also included being co-curator of “The Family of Man,” the greatest photography exhibition of all time (presented by the Museum of Modern Art in 1955). It included his being an integral part of the publication of three of the best-selling books in American history: A Baby’s First Year, The Family of Man and The World Is Young.

It included being offered the curatorship of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York when Edward Steichen was retiring; he turned it down. It included teaching classes at the fabled Institute of Design, Chicago. It included hundreds of adventurous and sometimes perilous assignments during the golden age of photojournalism. It included his favorite assignment — the documentation of his own family — at the time an avant-garde undertaking.

Above all it included an unparalleled humanism. Wayne’s work was all about explaining mankind to mankind. When he photographed a person, it was to give that person a voice, to convey not Wayne’s agenda, but the thoughts and feelings of the subject. When that happened, it was a successful picture.

Wayne spent his life in pursuit of this ideal. He was in many ways an old-fashioned American, in the very best sense of the word. Honor. Duty. Family. He understood human nature and possessed a wry sense of very cool humor. When I interviewed him in 2007, just to see if I could catch him off guard I asked him suddenly if he believed in a god. He glanced over and asked immediately, “What day of the week is this?” And, with a grin and a drag on his pipe, he said, “I believe in the goddess of luck.” Wayne also believed in humility, and while he was pleased whenever he sensed that the work he had made was being received in an atmosphere that fostered mutual understanding between people, he never cared for the associated trappings of being an “artist” or even the idea of fine art. “What the hell is fine art?” he said. “I think fine art is a day you’ve done very well.”

And despite the fact that he was highly accomplished — not only in capturing the human spirit and condition, but also in designing and printing — he eschewed extended discussions either of the content or craft of his pictures, claiming that “some people could damn near talk a picture to death!”

The highlights of the times I spent with Wayne include interviewing him for the 2008 PowerHouse monograph Wayne F. Miller Photographs 1942–1958; accompanying him on the trip to his 2009 retrospective at the Southeast Museum of Photography; spending the weekend with him and Joan at their home near Berkeley prior to my giving lectures on his career at the Tweed Museum in Duluth in October of 2012. The list goes on.

When I hear the phrase, “We shall not see his like again,” I think of Wayne. But before I leave you with the idea that he was a bit of a stuffed shirt, I should tell you that his sense of humor pretty much got him drummed out of Art Center. Wayne’s tongue-in-cheek execution of a particular assignment, complete with a beer label and a Chinese laundry ticket on the verso, by way of explanation, got him an invitation to continue his studies elsewhere, by the earnest and respected Tink Adams. Wayne did just that…on the Saratoga.

I invite any of you who would care to more fully appreciate this remarkable man and artist to forgive this informal and truncated homage and go online to witness an exquisitely produced seven-minute film that will tell you everything you need to know about Wayne Forest Miller: The World Is Young by Theo Rigby.

– Paul Berlanga