As the buzz around Tron: Legacy reaches a fever pitch leading up to its opening this weekend, our thoughts naturally turn to the original Tron and our beloved alumnus Syd Mead, whose designs are synonymous with the groundbreaking film.

A 1959 Transportation Design graduate, Mead is best known for his work on Tron, Bladerunner and Aliens, as well as for the creation of the V’Ger for Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

Mead

We caught up with Mead this week to find out what he’s been up to, and his thoughts on the new Tron.

Dotted Line: You’ve been busy. Tell us about your latest projects.

Syd Mead: My latest complete project was two food service designs and installations in New York City. FoodParc at ground level off Sixth Avenue and Bar Basque, the second level lounge and restaurant. My designs started, literally, on 8.5” x 11” sketch paper on the way back from New York after the first meeting with the architects, Philip Koether, Architects. The designs were faithfully reproduced by Koether’s expert team. Concept moves to completion through a complex symphony of cooperative expertise.

In the movie field, I’ve just completed pre-production contract designs for a young, recognized director for a movie title that is in progress. It is not my position to tell what it is.

Dotted Line: What have been the most enjoyable aspects of these projects?

Mead: They’ve all been enjoyable because you learn from each cooperative venture. The surprises come as the project moves from concept to idea to design. Adaptation to end format protocols, unwelcome shifts in focus by either capital sources for the project or intrusion into the process by those unfamiliar with the project intent yet given authority to “change.”

Dotted Line: Tell us about your current work in your new book, Sentury II. Has your focus changed over the years?

Mead: As a follow-up to Sentury, Sentury II covers the last 10 years of professional enterprise. My focus? It’s not changed for more than 50 years. The tools that accomplish the various desired results change; the methodology does not. The mistake I see in current rush to the computer is that the tool becomes more important than either the idea or the technique. This is disastrous.

Dotted Line: What interests you these days?

Mead: I have been interested in the development of a tool. We now have semi-intuitive “helper” software that anticipates habitual use of various software features. The hazard is that you come to depend on those “conveniences” to the detriment of genuine creative use of the exotic software being used. And, with many software applications, you aren’t given specific “turn off” directions. Another fascinating drift is the increasing insistence that since work is being done on a computer, the professional fee structure should be downgraded to a time/result formula rather than a realization that the computer implementation is a tool function, not a creative front-end function. Financial vectors in most professional account sources simply don’t recognize the difference between the two.

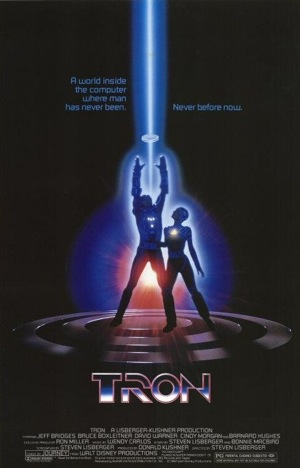

1982 poster for Tron

Dotted Line: With the buzz surrounding Tron: Legacy, our thoughts naturally return to the 1982 Tron that you worked on. Can you share with us what that job was like?

Mead: For the original Tron I designed the tank, the aircraft carrier (Sark’s command ship), the interior control set for the recognizer, the light cycles, of course, the release graphics of the movie title, the rotating CPU, the CPU approach field, the game arenas, the holding cells for the players, Sark’s command camp pit, Sark’s command pedestal and backup and several set drawings used to create the story environment including Yori’s apartment and the scenery design for the tank chase.

I was invited for lunch on the Disney lot by producers Steven Lisberger and Don Kushner and received a book of stuff that Steven already had with him. I started after about two or three weeks after contract matters had been agreed to by Disney.

I worked on Tron from my home studio, as I have with all the movies I’ve worked on. I always have several projects going through the corporation and being sequestered in an “on lot” cubicle doesn’t work. My function is meta-staff working one-to-one with the director and his immediate authority, the production designer.

The challenge was to realize what it was I was expected to do. Everything I designed, other than the release title graphic (which was an alpha version of the numeric graphic for the game arenas) was to be thought of as a three-dimensional interpretation of a two-dimensional digital display on the back side of a CRT. I also realized early on that computer constructs have no “weight,” and their position in three-space is non-gravitational—therefore offer chances to design elaborate constructs that retain their relative position without being physically connected. This was particularly evident in my design of Sark’s aircraft carrier.

Dotted Line: Were you involved with Tron: Legacy?

Mead: No, but I’ll be viewing the 3D Tron: Legacy at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences later this week.

Dotted Line: The first Tron was a technological leap forward. Do you think that this Tron: Legacy will do the same?

Mead: I have no idea. The 3D feature is a temporary reliance on glasses. Glass-less 3D and 360-degree holograms are the next major step in image display.

Dotted Line: What do you think of the new light cycle designs?

Mead: The new light cycle was designed my friend, Daniel Simon. It retains homage to my design with a more fluid configuration, which was impossible to accomplish with contemporary computer frame-by-frame generation in 1981.

Dotted Line: Do you think designing for 3D is different than for a regular film?

Mead: I don’t know why it would be. Any designer who creates vehicles, artifacts or even scenario environments has to think in 3D, a demand that has always been the case for hundreds of years. Translating a three-dimensional idea into a screen frame-by-frame image is a format problem, not a creative design problem.

Dotted Line: Did you ever imagine that your designs for that film would still be inspiring people 28 years later?Mead: No. One does not speculate on the duration, or the “future proof” on an idea. That phenomenon occurs as a result of acceptance by public acclaim.

Dotted Line: What are your future plans?

Mead: I will be working on pre-production of another movie which I cannot talk about at this time. After the start of the new year, my next big job will be to take some time off, cruise and finish my autobiography.

Dotted Line: What advice do you have for Art Center students who are inspired by your work and want to work in a similar field?

Mead: To be a successful, creative artisan one must be persistently curious, have a good memory and an appreciation of the world around, from the insignificant to the impressively large. Every design challenge relates to something that resonates with human society, human recognition, human sensibility and human desire for fulfillment. Designers are manipulators of iconic familiarity, producers of innovative response to specific direction and purveyors of original interpretation of what sometimes is the mundane. Success is the end result, not the in-progress activity.

Want more Syd? Check out the video below made by the Tribeca Film Institute:

2019: A Future Imagined from Flat-12 on Vimeo.

Pingback: Syd Mead on Campus Tuesday « Dotted Line | Official Blog of Art Center College of Design | Pasadena, CA | Leading by Design