Overhead view of a LEAP design storm. Photograph by Dice Yamaguchi

This is the second in our three-part Dotted Line series covering “The New Professional Frontier in Design for Social Innovation: LEAP Symposium,” hosted by Art Center College of Design Sept. 19–21, 2013.

LEAP’s Day One established the event’s tone, methodology, purpose and goals as well as a set of burning questions facing the field of social impact design professional pathways. The following morning, participants arrived eager to drill down into the issues that arose during the previous day’s workshops. Leap’s faculty team of facilitators and student teaching assistants were ready to continue guiding the second day of collaborative ideation sessions. Leap’s core programming team which included Karen Hofmann, Sherry Hoffman and Heidrun Mumper-Drumm, had mapped out a programming flow for these charrettes based on Art Center’s tried and true Design Storm methodology, which enabled intense collaborative study, brainstorming, and problem solving throughout the day.

Allan Chochinov (School and Visual Arts and Core 77) kicked off Day 2 of the symposium by gesturing at the battery of video and still cameras trained on the stage of Art Center’s Ahmanson Theatre: “It really puts pressure on the participants to create content worth documenting.”

Illustration by Ashley Pinnick

Chochinov had little reason to worry, as he would soon introduce Ben Weiss, an Art Center film student pursuing the Designmatters Concentration, who had come to screen a short highlight video featuring interviews he’d captured on LEAP’s opening day. The short film offered a snapshot of LEAP participants’ unfiltered observations about the challenges involved in establishing a viable career at the intersection of social impact and design. “What is the front line?” wondered Art Center Graduate Industrial Design student Daniel Bromberg.

His query was followed by those of several students who expressed some frustration at the professional roadblocks they’ve encountered in their efforts to secure entry-level positions. Then educator and social entrepreneur, Kyla Fullenwider weighed in with the following advice: “The opportunities to create your own path are really incredible. For people who are looking for a job description that fulfills every need they have, I’d say create that job for yourself.”

The tools of disruptive democratization

Cultivating that kind of pioneering enterprise may be sound advice. But when Jocelyn Wyatt, executive director of IDEO.org took the stage, she began steering the symposium back to the broader goal of laying the groundwork for creating an infrastructure that provides practitioners more opportunities to work effectively and collaboratively in this budding field. “Yesterday the brain trust spent about an hour and a half working on articulating a set of five themes to inform today’s groups,” Wyatt explained. “Ethics cut across all of them, as did shared language, tools, metrics and standards.”

Illustration by Craighton Berman

Wyatt then outlined the breakdown of topics that emerged from participants’ conversations on Day 1, to be addressed within Day 2’s workshops:

- Group 1: How might we capture and better communicate the value design brings for social impact?

- Group 2: How might we leverage emerging models and platforms to enable and sustain collaboration and partnerships?

- Group 3: How might we build a stronger network of social impact designers?

- Group 4: What are the imperatives in social impact design education?

- Group 5: How might we broaden access to design for social impact organizations?

Participants then disbursed into the classroom studios where the various groups would spend the next three hours designing strategies and scenarios that addressed these questions.

Group 2, the most popular of all the options, drew about 35 participants, who convened in the Film Department’s sound stage. The walls of the cavernous room were covered in large white sheets of paper that resembled fresh snow awaiting a hail of colorful Post-it notes from the massive Design Storming sessions in the forecast.

Robert Fabricant of frog design. Photograph by Alex Aristei

Participants huddled around LEAP braintrust member Robert Fabricant, VP of Creative, frog design, who ignited a probing discussion of the challenges facing designers as he framed the day’s goals. “We’re going to look at how you bring communities together through design and what we can learn from nonprofits, NGOs, community development organizations and other models,” he said. “The goal is to democratize the tools of design—and hopefully we’ll come away having figured out something nice and random and disruptive.”

The group’s path toward disruption, however, was anything but random. Fabricant along with Art Center faculty member Penny Herscovitch and the facilitation team organized the cohort into six smaller groupings, tasked with producing a model of success and failure in social innovation and suggestions for an “infrastructure for collaboration.”

After 30 minutes of ideation, the larger group reconvened, surrounded by the ideation boards, each with its own checkerboard configuration of fluorescent-colored notes. As the groups presented their findings, consensus began to form around a set of ideas that stressed the importance of a structured exchange of information between designers and those who employ them to create a more symbiotic relationship between industry and innovation.

- One group suggested creating an open-source network where designers and organizations share skills and resources to complete projects.

- Another proposed a formalized process for creating an endorsement for social impact designers and their projects—a kind of LEED certification for social good.

- There was much enthusiasm for the idea of creating a taxonomy of social impact design to educate both insiders and the uninitiated about the broad applications for design thinking.

- Along those same lines, another group focused on making designers more marketable with a graduate program from which they would emerge with an MBA and a design degree.

Using radical problem solving to foster daily magic

With much of the conceptual heavy lifting completed, the group broke for lunch and a panel discussion co-programmed with the Toyota Lecture endowed series, the Art Center Dialogues, entitled “Designing a Social Economy: Professional pathways in the emerging social capital market.” Lee Davis, scholar-in-residence, Center for Social Design, Maryland Institute College of Art, moderated the event, [watch panel video], which featured an inspiring lineup of heavy-hitters from the public and private sectors, each of whom provided interconnecting pieces of a larger puzzle linking design, solving intractable social problems and the entrepreneurial spirit.

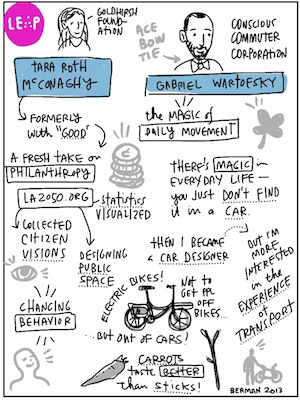

Illustration by Craighton Berman

Kanyi Maqubela, Venture Partner, Collaborative Fund, who articulated the growing symbiosis between design, innovation and tech startups. “I am a for-profit venture capitalist and I have four to 10 years to triple my money,” said Maqubela. “I also think of myself as a social innovator. Here’s how: We invest in tech companies. Technology predates science. The wheel was technology. Writing was technology. Technology is a tool that radically solves problems. Designers have optimism around radical problem solving. So the primacy of design entrepreneurs is at the top of our criteria for investing. And when I say I’m a technology entrepreneur, I’m actually a social impact investor.”

Next up was Tara Roth McConaghy, current President of the Goldhirsh Foundation and co-founder of Good, who explored the ways the nonprofit sector has become increasingly focused on innovation to seed social change. Her organization, which “connects the dots between the best emerging innovations and the financial, social and human capital to make them thrive,” boasts a staff of social innovators charged with helping social innovators. In essence, Goldhirsh is a model for integrating social impact strategists into its organizational structure.

The same could be said of Conscious Commuter Corporation, a start-up geared toward bridging the gap between public and private transportation with a fleet of sleek electric and folding commuter bikes. Art Center Transportation alum Gabriel Wartofsky co-founded the venture with entrepreneur, Bob Vander Woude, based on a folding motorized bike he designed as his senior thesis project at Art Center.

Gabriel Wartofsky hopes to change urban transportation with Conscious Commuter.

Photograph by Alex Aristei

But as with most successful innovations, Wartofsky’s inspiration for the project was rooted in personal passion and a desire to meet a human-centered need. “I grew up with biking hippies,” said Wartofsky, who developed a talent for spotting four-leaf clovers while pedaling around Washington, D.C., with his mother. “And I wanted to impact and change the way people move around and experience daily magic.”

Ever since Wartofsky’s bike was unveiled publicly last year, it has captured the imagination of sustainably-minded organizations and individuals. Orders have been flooding into the company’s Portland, Ore., headquarters ever since.

“Designing is solution seeking. Design is strategy,” Wartofsky mused. His closing remarks serve as a potent reminder about the purpose of social impact design at its most basic level. “Besides the experiential aspect of what we do, we’re also designing within systems. But even when we’re designing within that fuzzy space, our job is ultimately to communicate and better people’s lives and to make people happy. “

For the full LEAP experience, read our posts on Day 1 and Day 3.